Ten-year-old Amina leans on a sunken wood frame that forms a fence for a charcoal shop. She has come to buy charcoal with two other girls from a street tucked between ‘1,000 units’ residential area and Pegi in Kuje Area Council in Nigeria’s capital city, Abuja.

Frustration furrows the lines of her forehead: she has to go down the bushy path they had taken to reach here with “hastened steps” as their mother had instructed.

The other girls, who are a little older than Amina, crowd around her when approached by HumAngle, bearing a twinge of excitement and curiosity in their eyes. They had accompanied her on their mother’s safety instructions; run back home with Amina no matter what.

Only a week earlier, Amina’s mother, Zainab, had heard stuttering blasts that made the children jumpy throughout the night. The shrill sound of gunshots echoed around 11 p.m. WAT on September 5, throwing residents into fright.

For seconds, everything stopped. Then, a wail followed.

“That’s how they always come to raid. No one to stop them, not even the police,” says Zainab, looking wrung-out as she fixes her eyes somewhere far-off. The wrinkles around her eyes place her age at a little above 40.

The night passed quietly, but the dawn brought a new tragedy. She knew the gunshots were the growl of a criminal gang announcing their exit; “we live in terror of these gangs.”

The assailants had raided the home of Pastor Gabriel Oladapo, a civil servant who was away on a journey, and abducted his 45-year-old wife, Bukola and two daughters—Moyo, 17, and Glory, 14. Moyo was preparing for secondary school leaving exams at the time.

Their captors are now demanding ₦100 million ransom, Taiwo Aderibigbe, the Chairman, Pegi Community Development Association (PECDA), tells HumAngle.

“Pastor Oladapo is a poor civil servant. Where will he get ₦100 million from? How will his family get over the trauma?” the distraught community leader queries, frustrated at the criminality ravaging the once peaceful community he had moved into some eight years ago.

Like elsewhere in Northern Nigeria, kidnapping for ransom is the latest evil to befall Pegi, which has become inured to perpetual cases of armed robbery, break-ins and rape. Between 2018 and 2020, there were more than three kidnap cases with deaths recorded in the area. But abductions have become more indiscriminate. In March 2021, some days after HumAngle first documented the experiences of the ex-kidnap victims, another kidnapping took place.

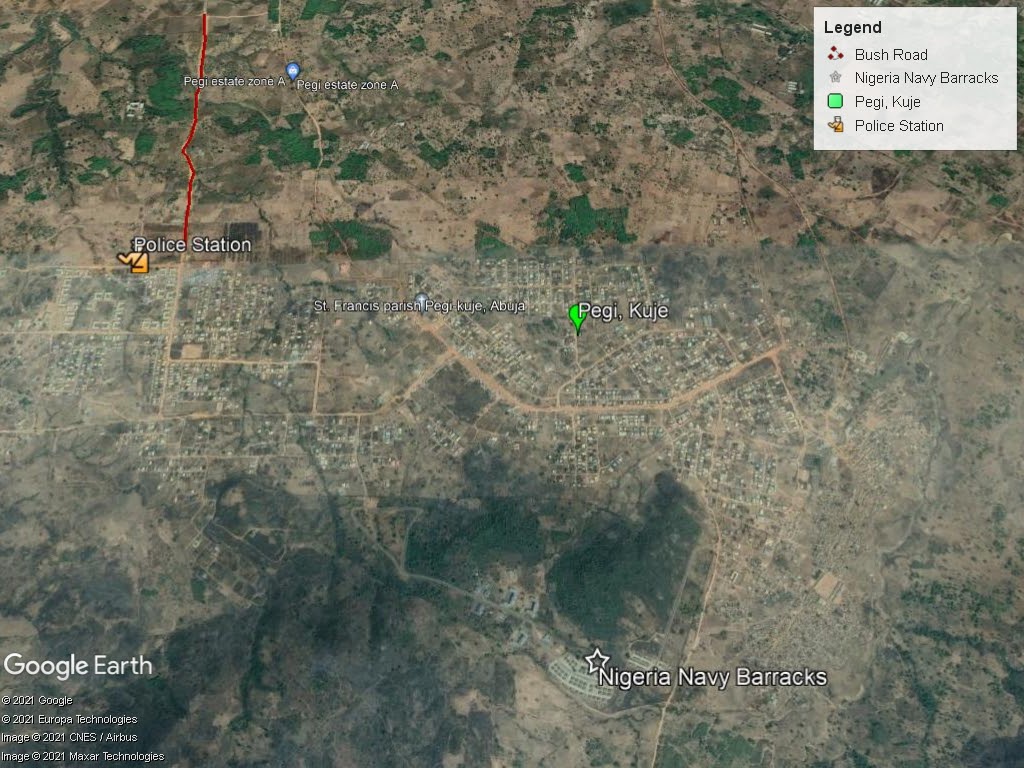

The rise in kidnappings has petrified many residents. Despite hosting a Nigerian Navy barracks, police station and outpost of Nigeria Security and Civil Defence Corps (NSCDC), Pegi under Kuje Area Council is not at peace.

Pegi, Pegged By Kidnapping

When Rilwan Majeed*, a civil engineer, was waylaid while returning home from work in the town centre in Dec. 2018, the naval base was about 15 minutes drive away from a dirt road called the Bush Road where he was abducted.

A Naval officer and some community members had tried to foil the attack but were immediately overpowered by the criminal gang, using assault rifles.

Majeed spent the first night in the hands of his captors, sitting on the bare ground, afraid to close his eyes. For days, he and two others were kept in tiny thatched huts in the middle of a forest on a hilltop, waiting endlessly for the moment they would return home. His family scrambled to gather money to free him.

“They (his family) never told me how much was paid, but it was not easy gathering it,” says Majeed over a phone call with HumAngle.

Majeed’s abduction was the first. It seemed an aberration for a community with a vast, mountainous area of 85,000 square metres where people, who once farmed despite holding government and private jobs, without fear. But since 2018, kidnappings and break-ins have been happening more frequently — at least once every four weeks, residents tell HumAngle.

The growing insecurity in the Abuja suburb has raised new fears for those who cannot afford the exorbitant cost of building or renting houses in the city centre, which is 45 km away.

‘Like A Nightmare’

For survivors like Shittu Adebayo trying to move on from a horrific chapter of their lives, leaving the community is their only option.

Like Majeed, Adebayo was returning from work on a February evening when three people carrying long guns suddenly shot at him.

When he left his car and ran for safety towards the community’s main entrance, the attackers were still on his trail shooting but turned back as he made it into the community. He had removed his white cloth and switched off his mobile phone during the chase.

“It felt like a nightmare,” writes Adebayo in a message shared with HumAngle.

He has since moved out of his house in the community because he could not deal with the trauma anymore. For Majeed, although his family is apprehensive about the physical and mental scars he endured during captivity, he is not moving anytime soon.

Those who stay say they are increasingly afraid of living in the area. Among them are those who work in the city centre; they are even more frantic about returning home in the evening.

45-year-old Felicia Anthony lives in constant fear and is too afraid to go outside her home anytime later than 7 p.m. Her husband has a welding shop in Kuje town, six kilometres away. One day when it was past seven in the evening, she told her husband to stay over at a friend’s place till dawn because “those guys are always lurking around the Bush Road, and it’s not safe to pass there in the night.”

Earlier in the year, Felicia’s sister (name withheld) and her (sister’s) husband were kidnapped and later released after an undisclosed amount was paid as ransom. The experience has left her edgy.

She gets so worried about her children’s schooling in Kuje that she keeps trying to convince her husband about moving the family to a safer location.

Abductions can create a collective trauma. Disorientation of the mind, fear and anxiety are all indications of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), says Dagona Zubairu, a professor of psychology and the immediate past director of Peace and Conflict, University of Jos.

“They may suffer depression and dissociative disorders,” he adds.

While healing may take some time, people must match emotional resilience with their physical resilience by bonding and seeking professional help from psychologists, he says.

The Famished Road

For residents, avoiding the Bush Road after 7 p.m. is part of the daily struggle to survive. The road is part of the highway that connects Pegi, Gafara, and Kuje but has been under construction without completion since 2011. It was a N676 million project commissioned during the past FCT administration of Adamu Aliero, alongside the construction of a public school (primary and secondary) and a poorly equipped health centre.

According to the community chairman, most kidnap cases occur on the abandoned 14 km highway.

In Oct. 2019, the residents protested against the increasing spate of kidnapping incidents, partly enabled by the uncompleted road. Their indignation was raw. “When we protested against insecurity and the road, the Minister of State for FCT, Rahmat Aliyu, gave promises. Again, it has become a political statement. The culture of the insincerity of the political class,” the Chairman asserts. “We waited endlessly for a response to see the magic that would happen. Nothing changed.” The government’s failed promises have taxed the residents’ consciences. They have watched friends or family die because of this.

At the health centre, a medical official who does not want her name mentioned says the bad road network has become a challenge even when referring patients with gunshot wounds to hospitals in the city centre for proper care. The centre lacks infrastructural facilities to handle cases beyond malaria and typhoid.

“It is always difficult to get vehicles that would convey our patients from here to the city. Commercial cars don’t usually come here. When we find one, the driver is often reluctant to go because of the bad road,” explains the medical official as she tends to a pregnant woman.

‘Business Not As Usual’

Asides from the bad road, the insecurity is driving local economic activity to the edge, hitting businesses hard, residents say.

Some artisans like Felicia, a charcoal seller, say they have reached “a saturation point” with the soaring crime rate and are now considering leaving because of the lack of protection. She wants a safer environment.

“Sometimes, you will just hear gunshots, and everybody will scamper off to get their children from school, leaving businesses behind while criminals loot their wares. It is not safe here at all. It wasn’t like this in the beginning,” she says.

Felicia describes how it was promising initially, with the Federal Capital Development Agency planning to build a modern market in the community after demolishing roadside shops, including hers. The traders were asked to pay N49,000 for registration but nothing came out of it. This claim was corroborated by Mama Jumoke, a hairdresser.

“They damaged my N500,000 worth of container I used here during the demolition. We paid the N49,000 they asked us to pay eight years ago,” Mama Jumoke adds.

All efforts to get a comment from Richard Nduul, the FCDA spokesperson, on the abandoned projects in the community were unsuccessful.

Experts say weak security infrastructure and legal system has made abductions lucrative in Nigeria. “The government must eliminate criminality by strengthening the justice and value systems. Equipping the armed forces with the right skill sets outside of combat is also very important,” says Seun Kolade, a professor of international development at the De Montfort University, United Kingdom.

“The government needs to show the criminal gangs the strength it has by carrying out a risk analysis of what is happening; then it must prioritise the risk by attending to each security threat as it comes.”

Some residents claim police officers do not engage with the kidnappers or criminals when they put distress calls across because they are not well-equipped.

“The other day when they robbed a house around here, one man in boxers ran to the police station for help, only for the officers to say they are not armed to face the criminals,” recalls Mama Jumoke.

When the perpetrators of abductions are arrested, the women say they are often released soon afterwards on the orders of “oga (corrupt officials) at the top.”

Residents say they have little confidence the suspects will ever be punished. Kunle Fakemi*, a resident and Civil Defense officer, says police are currently under pressure to release a man arrested last month for alleged involvement in a robbery case. The suspect’s family is exerting pressure on the police, he believes.

Similarly, the community chairman says the judicial system needs to make more effort to ensure suspects are prosecuted.

President Muhammadu Buhari has said repeatedly that his government is doing all it can and has put more resources into anti-kidnapping efforts. While the military offensive has been solely against terror gangs committing mass abductions in the Northwest region, there has been little focus on the criminality ravaging the seat of power.

Magit Solomon, the district police officer of Pegi Police Division, refuses to comment on the security challenges in the community; instead, he directs the reporter to the spokesperson of the police in the FCT, Josephine Adeh. Adeh similarly declined phone calls and text messages sent to her.

The community chairman, Aderibigbe, says the community has employed the services of local hunters: “We may have gotten positive results, but it is not enough as everybody’s hands must be on deck.”

“We are calling on the armed forces, the FCTA, to rejig the security and comb the mountains that serve as camps for these criminals. As well the judicial system and law on terrorism and criminality should be activated to prosecute apprehended suspects.”

This, he says, will give succor to the victims of sad incidents.

(Some names in asterisks have been changed at the interviewees’ request.)

This story was produced in partnership with Civic Media Lab under its Grassroots News Project.