By Kelvin Ololo

One of the first messages called him a “failed writer.” Others warned him to stay out of Calabar. By the third day, Ogar Emmanuel Oko, a writer and former president of the Nigerian Union of Campus Journalists, found his life nearly in turmoil.

His offense? Criticizing Governor Bassey Otu’s claim that people were defecting to the All Progressives Congress, APC, because of President Bola Tinubu’s performance.

In just a few hours, the backlash escalated from insults to threats, turning Oko into a symbol of the shrinking space for free expression in Cross River State.

Cyberbullying is fast becoming a strategic tool for silencing dissent in the state. Activists, journalists, and even ordinary citizens now face coordinated online harassment for criticizing those in power. Oko’s case is just one of many, reflecting the rising intolerance for dissent and the growing use of digital intimidation as a weapon of censorship.

Experts say this troubling trend mirrors a broader national pattern. “These harassment campaigns are not random,” says Thomas Ifebude, a media rights advocate. “They are designed to isolate, humiliate, and ultimately silence anyone who challenges the political status quo.”

Digital rights organizations like Paradigm Initiative have documented how online platforms are increasingly weaponized by political loyalists, often acting as digital enforcers to intimidate critics and control public narratives. These actors operate with near-total impunity, especially when backed by state power.

Where It Began

On April 28, 2025, Oko published a Facebook article titled “A Sour Lie from the Sweet Prince,” challenging the governor’s statements. Within minutes, the threats began.

“Our governor is an ordained apostle. Apostles are sanctified people. They are called to truth, not to lies,” Oko wrote. “Yet, our governor, new to the apostolic order, has told not just a lie, but an expensive lie. A lie so foul it reeks like the open dumpsite at Lemna — sharp, pungent, contaminating the air and choking every honest breath.”

He ended the post with: “The people deserve the truth, not a sanctified deception. History watches. Heaven listens.”

The post has garnered 171 comments, five shares, and 45 likes as of June 9th, 2025.

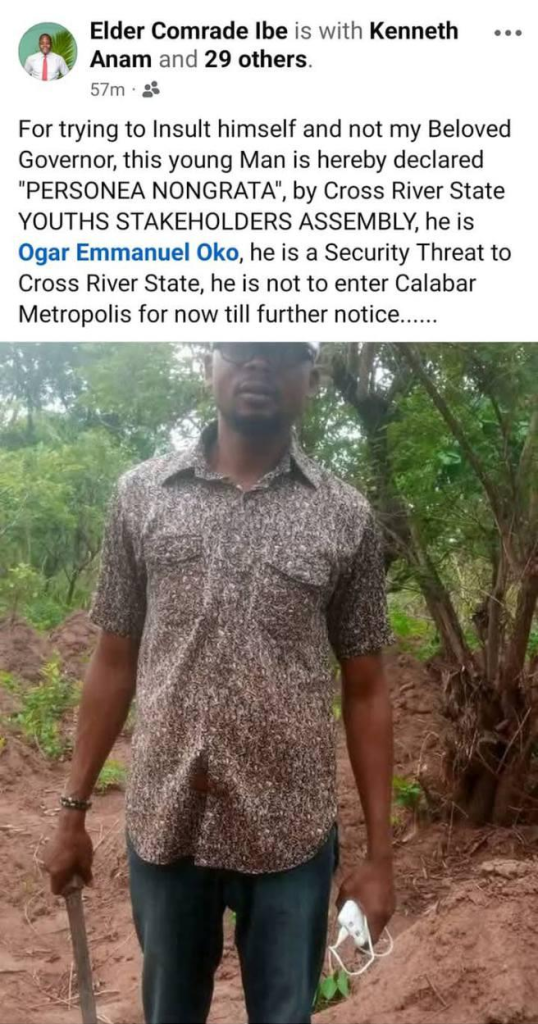

“People I didn’t even know started tagging me in hateful posts,” Oko told CrossRiverWatch. One post read: “For trying to insult himself and not my beloved governor, this young man is hereby declared persona non grata by the Cross River State Youth Stakeholders Assembly… He is Ogar Emmanuel Oko. He is a security threat to Cross River State. He is not to enter Calabar Metropolis until further notice.”

The post, which included a picture meant to mock Oko, was published by an account named Elder Comr. Ibe, Secretary to the Chairman of Calabar Municipality and a staunch APC loyalist. The governor’s Special Adviser on Digital Media, Citizen Ekanem, added fuel to the fire with his own Facebook post: “I repeat, that act of insolency displayed by one irresponsible person called Ogar Emmanuel Oko, he does not worth my response.”

Others joined in, calling Oko “someone who lacks proper upbringing,” “a sponsored writer,” “a threat to the state,” “a disrespectful fellow,” and “an irresponsible person.”

Harassment Spills Offline

Soon, the bullying extended beyond social media. “People would point fingers at me in public,” Oko said. “Someone even withdrew a contract we were working on because they feared being associated with me.”

He reported the threats to the police but says no action has been taken. “I am shocked that nobody has been invited for questioning or held accountable for these attacks,” he said.

Oko’s experience is far from isolated. Esther (not real name), a Mass Communication graduate, recalled deleting her Facebook account after being harassed for criticizing former Governor Ben Ayade.

She said she felt helpless, especially after Agba Jalingo and other writers were arrested. These attacks follow a familiar pattern: smear campaigns, name-calling, public shaming, and coordinated trolling, often from accounts linked to political loyalists. Posts typically include veiled threats, sometimes amplified by aides or official platforms.

Others like Dr. Peter Inyali, a former lecturer was assaulted by state actors, while Ifere Paul, and Joseph Odok Esq, were trailed, arrested, detained for days and weeks respectively. Mr. Odok was even charged to Court for treasonable felony and spent weeks incarcerated, before his release. He was eventually discharged and acquitted.

In 2015, Mr. Ifere Paul, a stalwart of the All Progressives Congress, berated the performance of Governor Ben Ayade and said he fared worse than his Rivers State counterpart, Nyesom Wike, after 100 days in office. This sharply pitted him against aides of the Governor, which would take a twist he never expected.

Between 2016 and 2017, an altered image of him with two horns on his head was circulated by Eval Asikong (a junior spokesman) and other aides of the Governor, who described him as “the devil.” This was in response to Mr. Ifere’s description of Governor Ayade as a “four-horned devil.”

An image of him shirtless, while eating moi moi (a snack produced from beans) was also circulated with the tag “419,” by Ajie Paul (another aide), which refers to a section of the criminal code that deals with fraudsters. Another image of someone practicing open defecation was circulated on Facebook, with narratives describing him as “uncivilized.” Most of the posts were deleted after these aides were railroaded into joining the All Progressives Congress following the defection of their principal.

Mr. Declan Ogar Genesis, an aide on youth affairs, went further to describe natives of Yakurr Local Government Area, where Mr. Ifere hails from, as “cannibals,” which drew condemnation.

“Victims are not just ridiculed; they’re professionally and psychologically isolated,” says Tosin Makinde, a political analyst based in Lagos, Nigeria. “This erodes civic engagement and drives people into silence.” She adds that the absence of meaningful consequences for perpetrators emboldens further attacks.

This is the case with a lawyer and lecturer, Joseph Odok, whose troubles came from many fronts. Criticizing the Governor, his Vice Chancellor, and others meant it was a matter of time before state apparatus was utilized to silence him.

In October 2016, his vehicle was impounded and was released after he claimed the Chief of Staff to Governor Ayade sent him NGN250,000 so he won’t take the matter to Court and to defect to the People’s Democratic Party and stop his criticism.

By April 2017, he received two queries from the University of Calabar, which led to his suspension, and a month later, he was arrested for possession of weapons to bomb the institution. The case was never successfully prosecuted. But his fortunes will only turn out worse.

Less than three months after he was recalled from the initial suspension, he was re-suspended in January 2018 for publishing a “plethora” of posts with “wild” and “unsubstantiated” claims against the Vice Chancellor.

By September 2019, after being detained for trying to bail his wife at the Iddo Police Station in Abuja, he was hauled to Calabar, where the police charged him with treasonable felony, terrorism, among others, with Chief Martins Orim, then Chief of Staff to Governor Ayade, being the nominal complainant.

While incarcerated, another case filed by the Vice Chancellor of the University of Calabar never went to trial. He was remanded at the Medium Security Custodial Center and was admitted to bail after spending 117 days incarcerated. He was subsequently discharged and acquitted.

Real-Life Impact

For victims like Esther, the toll is deep. She gave up her dream of becoming a journalist. ” I don’t think I can still talk about any government in this country in terms of accountability, if it’s government, count me out. I cannot risk it.”

Oko now lives cautiously. “People kept pointing at me, calling me names, questioning my audacity to talk about the governor,” he said. “Some have called me privately, persuading me to tender an apology to the governor.”

He also revealed that a contract he was working on was withdrawn shortly after his article was published.

“The person said he cannot continue with me so that he will not lose out when the governor comes to know that he is working with me,” he said.

On April 7th, 2018, Dr. Inyali, in what he described as an assassination attempt, was attacked by state actors while attending a funeral in his native Obudu Local Government Area after heated arguments on social media after his criticism of then-Governor Ben Ayade. Before then, he had been accused of fabricating falsehoods and called a hatchet man of the APC who spread misinformation against the Governor.

“Immediately I arrived at the funeral grounds, I started noticing some unusual movement around me,” he said, adding that they repeatedly told him, “You know how to write about the Governor, we will mend you today.”

Inyali had to transfer his services and relocate to Abuja, the Federal Capital Territory, where he continues to practice journalism among other business concerns.

In Ifere’s case, he was arrested in Abuja, the Federal Capital Territory, and transported by road to Calabar, where he faced trial for different reasons. The cases were abandoned and subsequently struck out, with Mr. Ifere walking free. In July 2016, he was declared wanted by the Attorney General, Joe Abang Esq. However, that was dismissed by the Police, who said he wasn’t a wanted man.

Ifere said he was undeterred, he continued with his criticism of the government and said the ordeal only made him stronger and popular. However, he found Calabar too hostile and relocated to Abuja, the Federal Capital Territory, for a while.

On September 4th, 2017, Odok was stabbed at a social facility in Calabar, with security aides of Governor Ben Ayade accused of being involved in the incident. The matter was abandoned after a while. He lost his job at the University of Calabar while he was incarcerated. And, upon admission to bail, fled Calabar with his family for fear of further reprisals.

Joseph Odok, after he was stabbed in Calabar, with security aides of Governor Ben Ayade mentioned as principal suspects

Nigeria’s Cybercrimes Act of 2015 (amended in 2024) criminalizes cyberstalking and bullying, but enforcement remains selective in Cross River. “Penalties include up to 10 years in prison and ₦25 million in fines,” said Barrister Oluayemi. “But prosecutions are rare — especially when perpetrators are politically connected.” The Criminal Code Act and Penal Code Act also prohibit threats and defamation, but in practice, the law offers little recourse for victims of politically motivated online abuse.

Despite the attacks, Oko insists he won’t be silenced. “Speaking is our right. If we keep quiet, our children will stand on our graves to lay curses on us,” he said. “If we want a better society for ourselves and the generations to come, then we must speak up but constructively.”

This report is produced by CrossRiverWatch in collaboration with the Centre for Journalism Innovation and Development (CJID) under its Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation (SLAPPs), as part of a project documenting issues focused on press freedom in Nigeria.

Leave feedback about this