By Patrick Obia

OBANLIKU, CROSS RIVER: For many years, the Becheve people in Obanliku Local Government Area of Cross River State raided their forest for firewood, meat, and food.

The clan of 16 communities of primarily farmers and hunters did not know better. For them, the forest was a gift from God, and they were ready to bring it down, including for agricultural expansion and rapid urbanization.

“Our people didn’t know the consequence of what we were doing, and so we were cutting down trees, burning bushes, with reckless abandon,” said Onom Sunday Ichile, the clan head of Becheve.

The actions of the communities, which are host to the famous Obudu Mountain Resort, contributed to the depletion of Nigeria’s forests. Between 1999 and 2004, Nigeria lost 2.38% of its forest yearly, amounting to an average of 260,000 hectares of forest per year.

In 1991, the total forest cover in Cross River state stood at 7,920 square kilometers. By 2008, it had declined to about 6,102 square kilometers. As the forest depleted, Becheve became hotter.

“The ranch ran a temperature of 9 to 23 degrees centigrade at the highest, but now, it can rise to 25 to 26, meaning climate change is really entering because of deforestation,” said Lawrence Osong, Project Coordinator of the Africa Research Association Managing Development in Nigeria (ARADIN), a community-based nonprofit organization working to conserve the forest and support community livelihoods.

Research-Borne Intervention

In 2004, ARADIN entered Becheve to research how and why the temperature at the ranch, one of the highest plateaus in Nigeria, was constantly rising.

“During our research work, the result indicated that the temperature rise was a result of the depletion of the forest – cutting down of trees, sand mining, and hunting,” said Mary Undebe, ARDIN’s Project Administrator overseeing the project in Becheve and other communities.

“And these vices were brought about because of poverty. Poverty and deforestation go hand-in-hand; when people are poor, they get into the forest to cut trees to make money for a living.”

Based on these realities, the organization concluded that supporting the community with conservation efforts without gradually removing their dependence on the forest through economic support would be a waste of time.

So ARIDIN trained some community members in animal rearing, soap making, and vegetable gardening. It taught others about garri (cassava flakes) processing, storage, and marketing. It also provided them with soft loans to establish a cocoa-based cooperative society that gathers and sells cocoa.

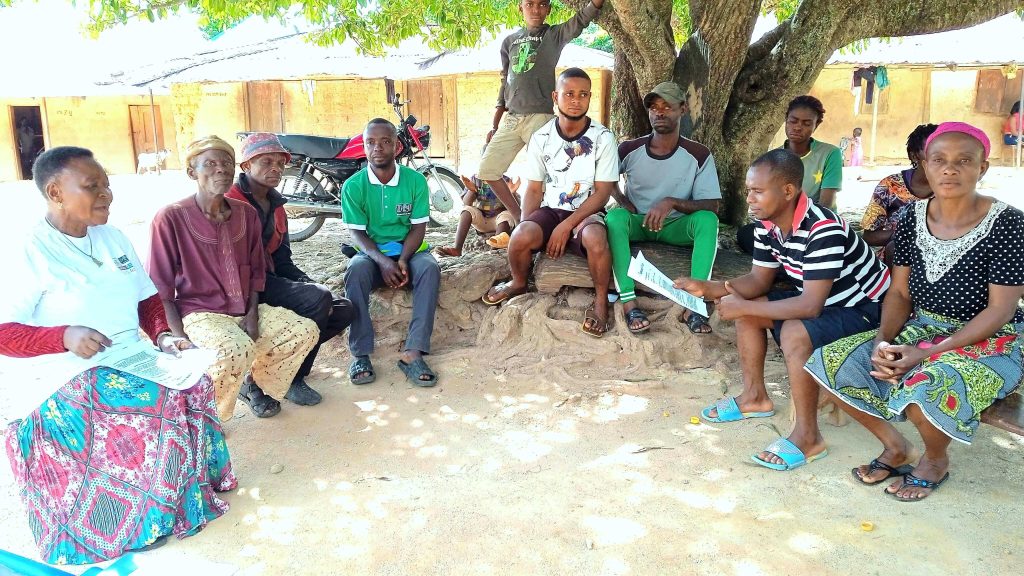

Next, among the empowered community members, ARADIN selected youths to form a Forest Management Committee (FMC) replicating ARADIN’s strategy in other parts of the State. This trained group of passionate volunteers serves as forest guards protecting their forests. There are 240 FMC members across 11 communities in the State.

“Later, we introduced tree planting, fire tracing, and the capacity building of the community leadership,” Undebe said. “We formed land use plans for them and so many activities regarding climate change mitigation.”

The land use plan, also called “assisted natural regeneration”, details how each community could restrict activities – farming, hunting, uncontrolled burning of fire, sawing of wood, and cattle rearing, among others – in forest areas.

A vital part of the plan is that the community maps out a new area for conservation every five years. During the period, nobody in the community is allowed to farm, hunt, burn, or cut timber in a certain area meant for conservation.

So far, ARADIN has assisted four communities in Becheve to replant about 65,000 trees and is targeting to reach 150,000 trees by 2025. Now the communities say they feel great since the intervention.

“The communities have regained the things that were lost, including our weather,” said Ichile, the clan head of Becheve. “We lost our forest, but they have (helped) replace the forest through the tree planting they have embarked on over the years.”

But challenges have threatened the sustainability of the forest recovery efforts, including the destruction of planted seedlings by cattle belonging to community members. The cattle often break the perimeter fencing constructed with barbed wires to access and feed on the nurseries.

“The indigenes have now taken advantage of their terrain and have gone full-time into the cattle-rearing business. But the cattle are trampling on all our seedlings,” said Osong, the Project Coordinator.

“They go to every side, so we provided perimeter fencing. But even with that, if you are not there on site, the herders will come and cut the barbed wires and allow the cattle to go in; it is giving us a big challenge. We had raised that with the council of chiefs in the communities.”

The council of chiefs has now given sanctions to herders in the plateau, ordering them to respect their range and never go into the regeneration.

This story was produced by Prime Progress with the support of Nigeria Health Watch through the Solutions Journalism Network, a nonprofit organization dedicated to rigorous and compelling reporting about responses to social problems.

Since You Are Here, Support Good JournalismCrossRiverWatch was founded on the ideals of deploying tech tools to report in an ethical manner, news, views and analysis with a narrative that ensures transparency in governance, a good society and an accountable democracy. Everyone appreciates good journalism but it costs a lot of money. Nonetheless, it cannot be sacrificed on the altar of news commercialization. Consider making a modest contribution to support CrossRiverWatch's journalism of credibility and integrity in order to ensure that all have continuous free access to our noble endeavor. CLICK HERE |

New Feature: Don't miss any of our news again.Get all our articles in your facebook chat box.Click the Facebook Messenger Icon below to subscribe now

Text Advert by CRWatch :Place Yours

Will You To Learn How To Make Millions Of Naira Making Special Creams From Your Kitchen?.Click Here

Expose Your Business And Make More Sales. Advertise On CrossRiverWatch.com Today

Leave feedback about this